Dear Friends of CCI,

Our September 2019 mega-delegation of American citizens were dazzled by the beauty of current day Russia and also horrified to learn what today’s grandparents and great-grandparents endured in the Gulag work across the USSR. It is reported that over 17,000,000 persons, mostly men, were worked to death in frigid camps throughout the USSR from the 1920 to the 1950s.

Much of this history had been closed off to Russian society. However, the new Moscow Gulag Museum makes the history abundantly clear. The FotoJournal below is but a tiny sample of what is housed within the Gulag Museum.

How could a vast country like Russia become normal again after such tragedy and loss for 30 years … knowing their own leaders turned on millions of them? Those decades had a mass effect on the entire population. They never knew when a knock at the door would come … and their loved ones would be taken away. When we arrived in the USSR in 1983, people on sidewalks carried a silent blank look on their faces like they were registering no one. There were no smiles, the buses were silent, metros were silent. Nearly everyone had a small book to read in their hands, usually the front and back covered neatly with a newspaper wrapping. No one looked to the left or right. Russian people, I learned at that time, had very few friends and didn’t make new friends … they couldn’t trust strangers for fear of being informed on. It then became obvious that most Soviets seemed to have small, tight inner circles. They invited us in, we suspected because we wouldn’t inform on them and would soon be gone. They loved practicing English. I began to think of these small groups as pods, “pea pods” …their insides were surrounded by a tough outer covering that was difficult to penetrate.

It became clear that insiders would die for each other if necessary. Each seemed to have very few friends. However, those they had were deeply dedicated to each other. The small nodes consisted of family members and a few friends they had known from school and university years. They trusted one another .. but none outside these small groupings.

Interesting thing was that some were quietly open to foreigners, particularly English speakers. In those years, all students studied Russian language, their republic language and a foreign language. Many chose English as their foreign language. We would quietly pass our citizen diplomacy cards to strangers. Sometimes they would catch up with us a block away. Others would quietly risk asking our nationality on side streets or parks. They would pass us their address on a scrap of paper and ask if we could come at an appointed hour, always mentioning to make no noise and speak no English. We would agree, flag down a car in the street and show up at the appointed time. This is how we developed our first small Soviet rolodex. We never gave out contact info during those days. Our tightly committed Center travel leaders increasingly took groups to different republics; with each new delegation our database grew.

It was clear to us that Russians were a bruised and wary people with good reason. Watching their gradual move toward building bits of trust with each other has been interesting to observe. Today on the streets they look very much like westerners, except a little more tidily dressed and groomed. Still Russians seem a bit more wary than we Americans, with good reason.

Russians on today’s streets are far more open and spontaneous than their parents were at their ages. As for Russia’s 50 – 60 year old age group, I was approached earlier this year to meet with some of our CCI entrepreneurs to discuss “Open Communication” and how they can achieve open-ended business communication with any and all persons they meet. I look forward to this process starting in 2020. We at CCI learned so much regarding the mechanics of “closed and open communication” during the trainings of the 6,000+ entrepreneurs in American companies, that I think we will be useful to this age group.

Russians are a very deep and complex population of people compared to Americans. They carry the legacy of past generations to a much greater degree than do we. For decades they have been far better educated than most of us. Yet, they and we alike admit that we find common ground more easily and enjoy each other more than we do any other peoples.

As a younger Russian woman said decades ago, “We are two halves of the whole: You Americans are like butterflies- you flit here and there with confidence and we admire this; we Russians have deep roots in our soil and our souls, we bring depth into our relationships with you.”

Sharon Tennison

Center for Citizen Initiatives

FotoJournal from Moscow- The Gulag Museum

September 6, 2019

By Mike Metz

We visited a museum to honor the victims of the gulags, a system of hundreds of slave labor prison camps established and operated by the Bolsheviks, that lasted forty years. Millions of prisoners, some gathered up in the dark of night with a knock on the door, quickly “convicted” by sham courts and sham judges, often with fabricated evidence and lies, branded “enemies of the state.”

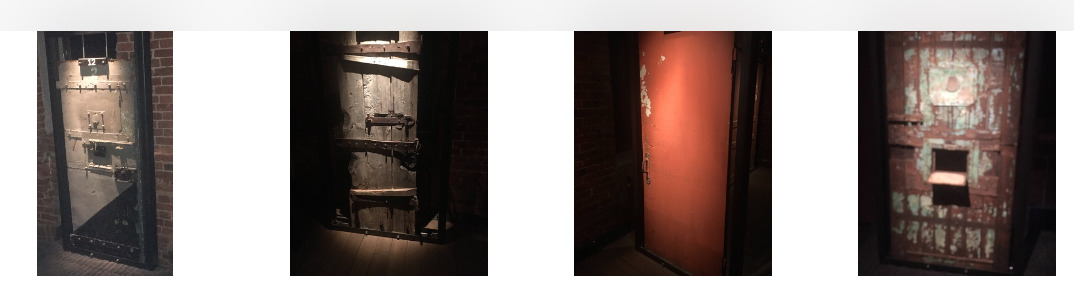

The first exhibit was of doors. Doors of incarceration, taken from jails and prisons and interrogation rooms and the camps themselves, from across Russia. Doors from which those who passed through often never returned.

Nearly every family in Russia was affected. Arrest quotas were established. If officials did not meet their quota, they too could be taken.

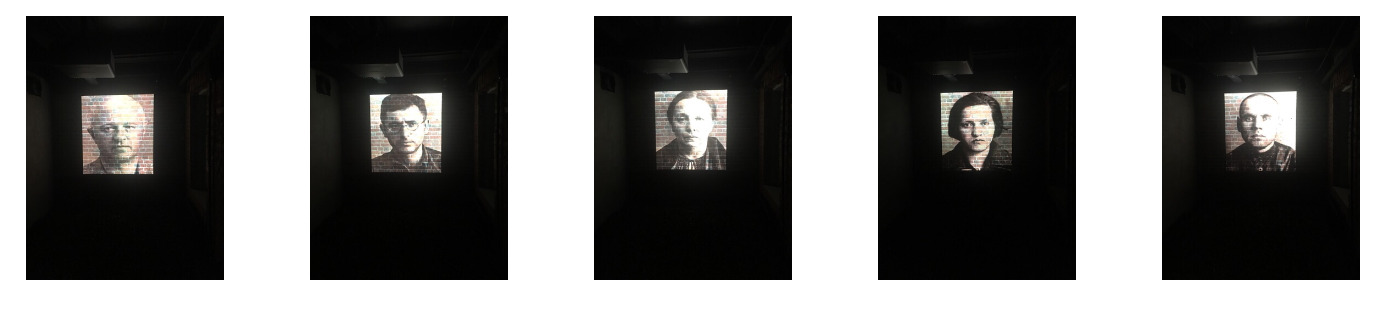

Much of the museum consisted of oral histories of the prisoners, often told by family members. Each included a picture of the victim. Many had letters sent home, asking for food to be sent.

To think that humans can do this to each other. And to think of the psychological impact of such a crime upon a nation.